The United States has deep inequalities, with its wealth clustered in certain neighborhoods, towns and cities. Many other places struggle with unemployment, elevated crime rates, and minimal access to public services.

How widespread are these disadvantaged communities, and how can governments help create more jobs there? Tim Bartik, an Upjohn Institute senior economist and leading expert in place-based policies, answers both questions in a new brief for the Washington Center for Equitable Growth.

Governments spend about $80 billion per year on job creation, Bartik shows, most of it dedicated to tax breaks for large businesses. His brief instead highlights cost-effective, evidence-backed strategies to improve employment specifically in distressed areas – places where the share of prime-age adults holding jobs significantly lags the U.S. average.

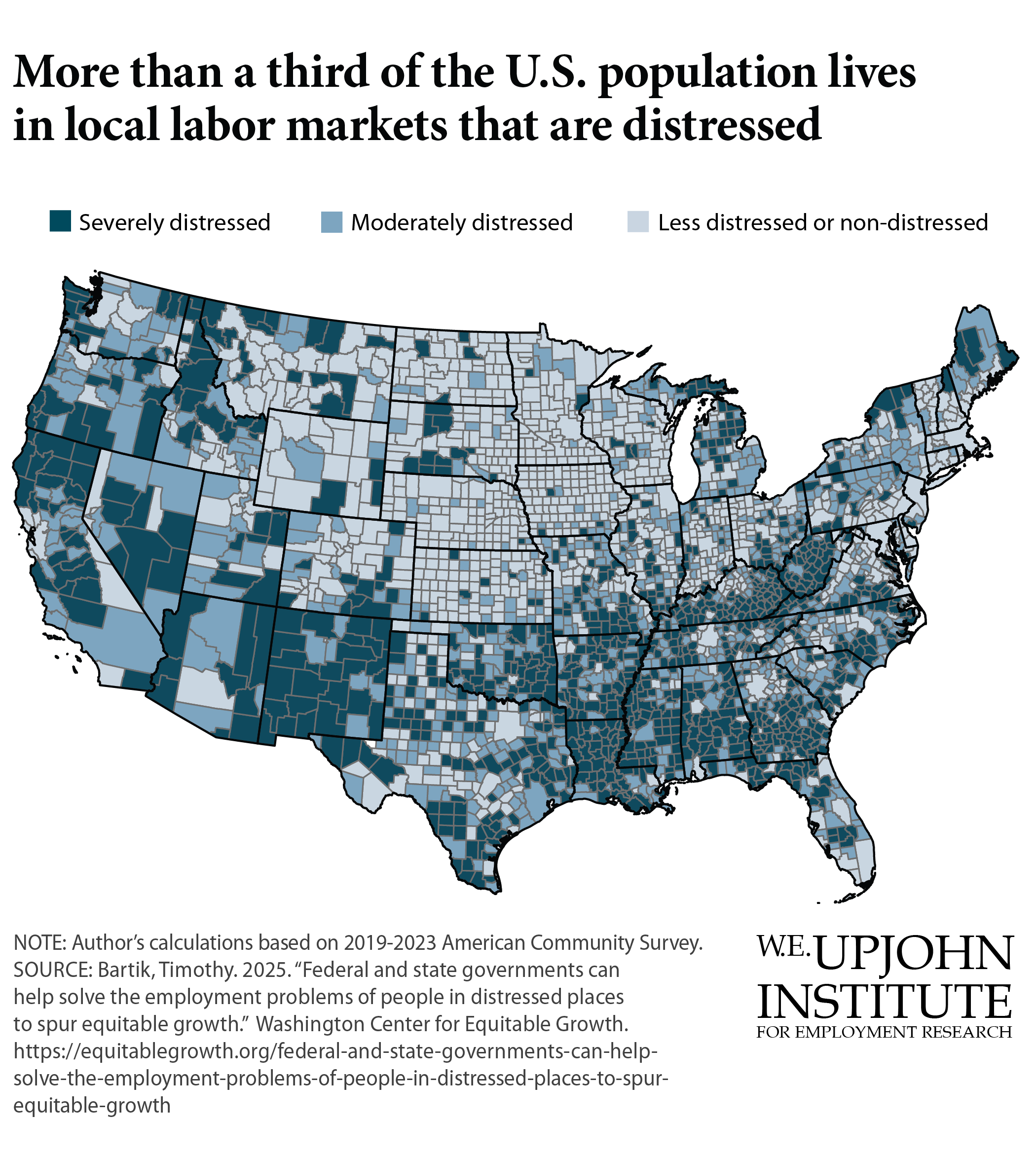

Bartik’s analysis of Census data finds that more than a third of Americans live in distressed places and 1 in 10 in “severely distressed” ones. Residents in these places struggle to find good jobs. Another 28 percent of Americans live in “moderately distressed” areas, where job finding is only slightly easier.

Each year, governments provide a smaller sum, about $10 billion, to “customized business services,” programs tailored to the needs of an industry or even a specific company. These services could include building a research park for a fledgling tech industry, building roads to help move supplies to a new factory, or specialized job training programs at community colleges to promote a skilled workforce pathway for a particular industry.

Customized business services – which cost between $78,000 and $155,000 per job created – have a greater return on investment than business tax incentives, which cost roughly $436,000 per job, Bartik finds. Governments could spend their economic development money much more effectively by focusing on these more localized programs.

Meaningfully addressing the employment gap between distressed and more fortunate places would require significant government investment: around $20 billion per year for at least 10 years, Bartik estimates, much more than Congress’s recent efforts to fund customized job development programs.

State and local governments can still make a difference with their limited resources, Bartik argues. By cutting less-efficient business tax incentive programs by less than a third, governments can invest $300 per capita in their most distressed communities, creating more jobs without increasing taxes.

Helping people in distressed communities requires a new approach, and participation from local leaders, to ensure that programs meet the needs of their businesses and their workers, Bartik concludes. Long-term, flexible investments focused on local considerations can give residents of the most distressed communities a better chance of getting good jobs.

Related Research

- Smart targeting of jobs at distressed places offers cost-effective, lasting effects

- The illustrated case for targeting local job creation on distressed labor markets

- Policy brief: Should we target jobs at distressed places, and if so, how?

- Working paper: Should place-based jobs policies be used to help distressed communities?

- Working paper: Long-run effects on employment rates of local demand shocks, across and within local labor markets