During World War II, the U.S. government funded the construction of factories across the country to quickly scale up wartime manufacturing. These new factories' benefits stretched far beyond the war's end, improving local job markets for decades.

New research funded by the Upjohn Institute's Early Career Research Awards program explores how creating high-wage manufacturing jobs increased upward mobility for local workers. The research focuses on counties outside of the largest prewar urban manufacturing hubs where factories sprang up for the war effort.

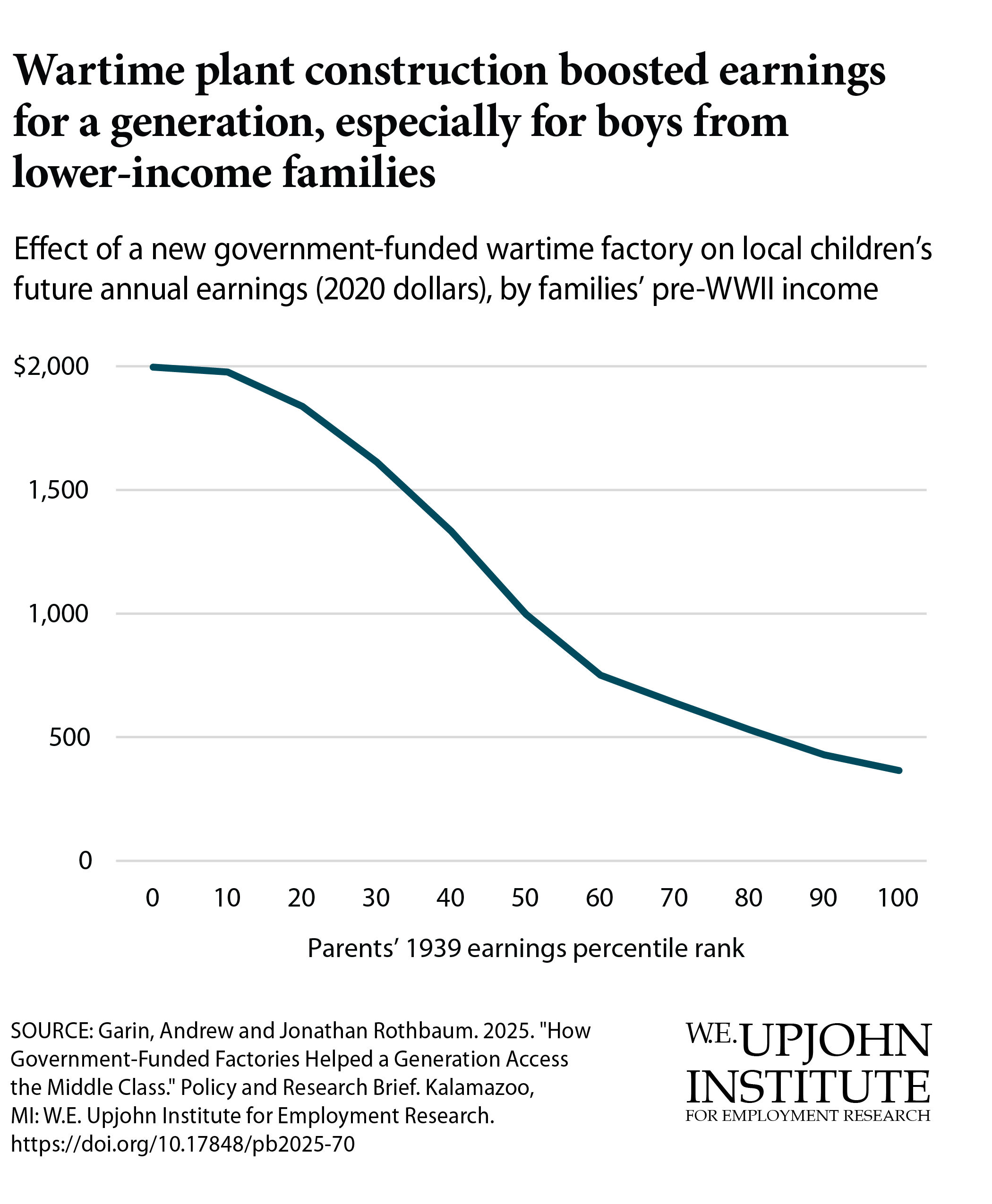

Boys growing up in counties where new wartime factories were built went on to earn more than did their peers from counties without new factories. On average, they earned $1,200 more, in 2020 dollars, per year over their adult careers.

The factories' local benefits, researchers found, came in providing high-paying jobs that gave workers from disadvantaged backgrounds opportunities to get ahead. Those who grew up in the poorest families got the largest boost, around $1,800 per year, while those from the richest families saw no effect.

Andrew Garin of Carnegie Mellon University and Jonathan Rothbaum of the Census Bureau describe their research in an Upjohn Institute working paper and policy brief, "How Government-Funded Factories Helped a Generation Access the Middle Class."

The research adds historical perspective to the literature on place-based economic development. Many studies have explored local effects of sudden factory closings, but few have focused on sudden factory openings.

Some lessons from the research apply to current debates, the researchers conclude, especially the importance of creating paths to high-paying jobs for locals. However, they caution that opening a comparable factory today would not have similar effects on local employment and wages.

Domestic manufacturing now offers far fewer opportunities for people from disadvantaged backgrounds to get ahead. With the dwindling influence of labor unions, the increasing use of automation and greater overseas competition, manufacturing jobs don't provide the same ladder to the middle class they once did.

In fact, other research has found that, while recent factory openings have increased the share of local jobs in manufacturing, they haven’t raised average wages at all.

The findings don't mean that place-based economic development can't succeed, Garin and Rothbaum conclude, but there is also no guarantee that attracting manufacturing plants to a region will benefit the local workforce. Citing research from the Institute’s Tim Bartik, they note that policies to encourage local job growth depend crucially on the details.

The Upjohn Institute's Early Career Research Awards provide resources for researchers within six years of earning a Ph.D. to carry out policy-related research on employment issues.