By Michael W. Horrigan, President, Upjohn Institute for Employment Research

September 29, 2025

In recent weeks, the Trump administration has argued that the size of revisions to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) payroll jobs data are too large to be believed, are evidence of manipulation for political purposes, and underscore the need to modernize BLS.

The purpose of this essay is to explain why BLS employment data are revised and to argue that their sizes are indeed concerning, not because of political manipulation but for what they mean for the U.S. economy. I also want to press the case that BLS does need more resources to continue to improve the quality and timeliness of its estimates.

For full disclosure, I worked at the BLS for 33 years, running the inflation and employment/unemployment measurement programs for 10 and 6 years, respectively. However, this is not simply a spirited defense of family turf. Rather, as my training at BLS taught me, I want to address my concerns in a manner that is as objective, nonpartisan, and transparent as possible, including noting where BLS can make improvements in both data collection and reporting.

The administration’s concerns have focused on the Current Employment Statistics (CES) survey, particularly two recent revision episodes: those announced in the July 2025 Employment Situation release and the preliminary benchmark revisions announced on September 9. Let’s examine each in turn.

Revisions to the May and June payroll estimates

In the July release, BLS revised its estimate of payroll employment change for the prior two months sharply downward:

- May’s gain was revised from +144,000 to just +19,000, a reduction of 125,000.

- June’s gain was revised from +147,000 to +14,000, a reduction of 133,000.

These revisions were striking. Their size led the White House to accuse BLS of manipulation and coincided with the dismissal of then-Commissioner Erika McEntarfer. What did not escape the notice of economists, however, was that the revisions signaled a significantly weakening labor market, including a first closing employment change of only +73,000 jobs in July.

Why do revisions occur?

The CES is a large survey—121,000 employers covering about 631,000 worksites—and it takes time to collect responses. BLS allows three months for reporting. About 60 percent of firms respond by the first closing (the basis for the initial release), 90 percent by the second, and 95 percent by the third. Revisions simply reflect the incorporation of these later reports, which improve accuracy.

First-closing response rates have slipped from around 70 percent pre-pandemic to 60 percent today. That decline increases variance in the preliminary estimates. For June 2025, about 40 percent of the downward revision from first to second closing came from late reports in state and local government education. Other industries also revised downward, producing the overall –133,000 change.

Seasonal adjustment also contributes to revisions. Because employment follows predictable seasonal patterns—teacher layoffs in summer, holiday retail hiring, winter slowdowns in construction—BLS adjusts to isolate true cyclical trends. Between the second and third closing, when over 90 percent of responses are in, most revisions come from re-estimating seasonal factors with the new data.

Are these revisions historically unusual?

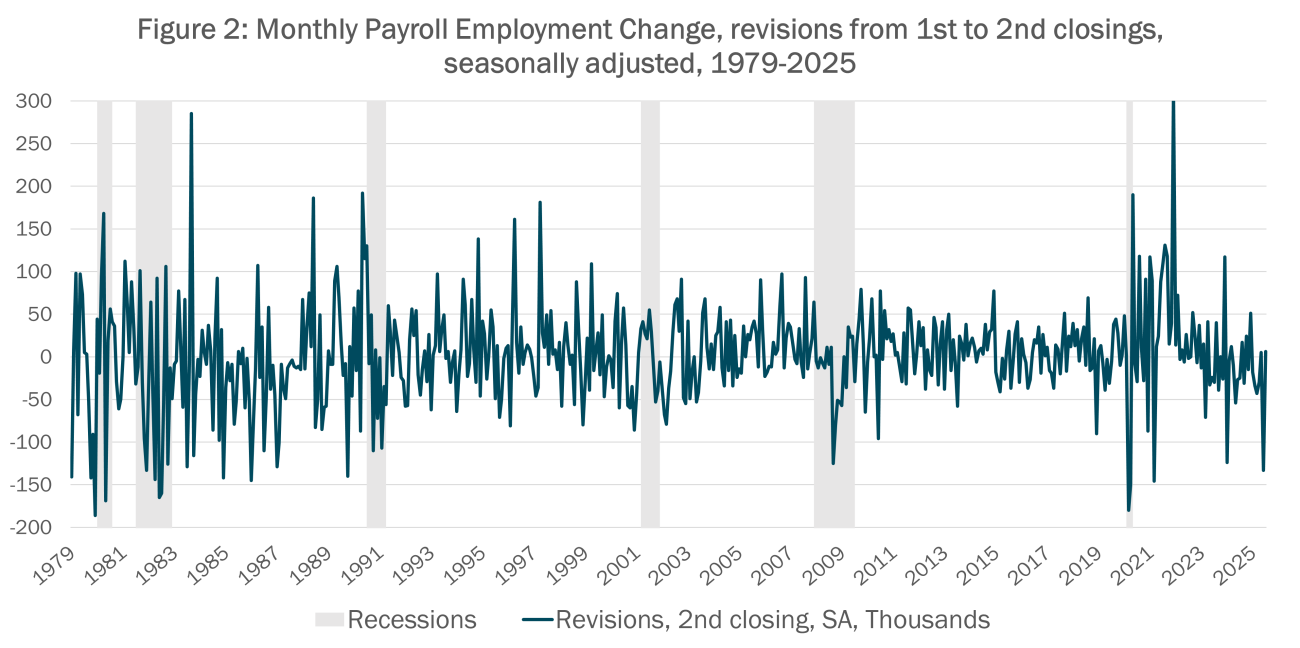

The administration has argued that these were the largest revisions since 1968 (Kevin Hassett, Meet the Press, August 3rd, 2025). That is not quite accurate. The June downward revision of 133,000 was the sixth largest in absolute value since 2003, when probability-based sampling was introduced into the CES. However, if you exclude the pandemic months, it was in fact the largest since 2003 (see figure 1).

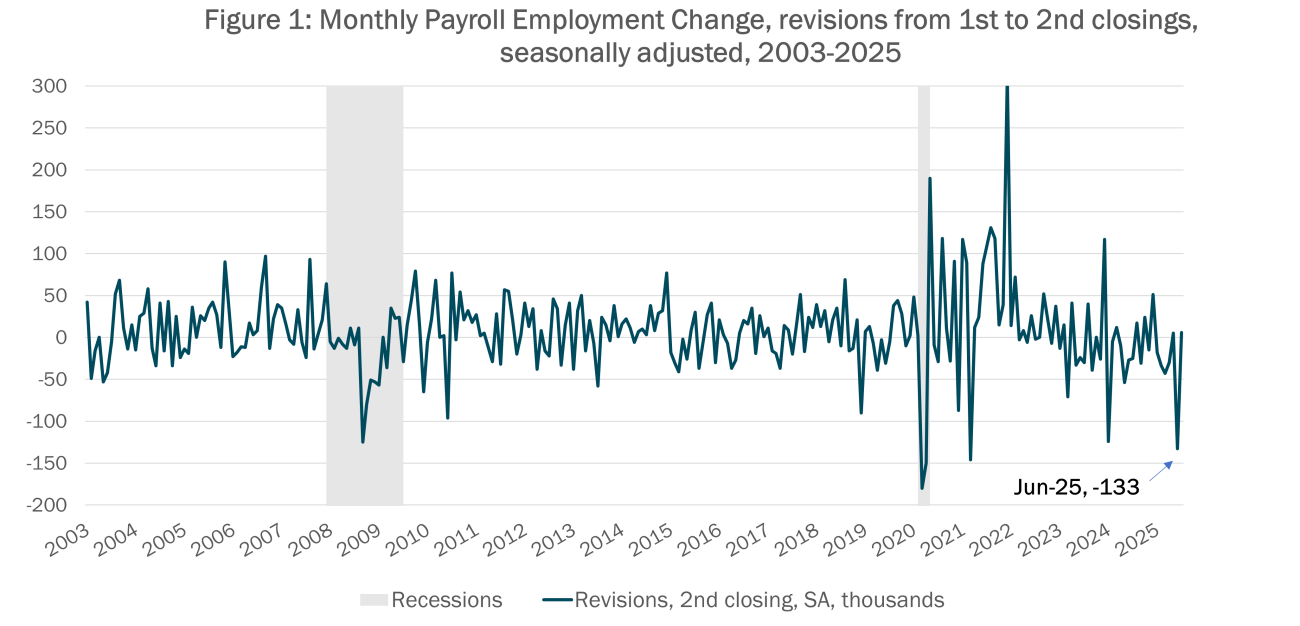

Prior to May 2003, CES used quota-based sampling, with the goal of achieving 40 percent employment coverage for each reporting month. Revisions were more variable under quota-based sampling, and the June 2025 revision from first to second closing ranked 23rd in absolute value since 1979. If you only include negative revisions, the June 2025 revision ranks 14th (see figure 2).