January 7, 2026

A new study looks, for the first time, at the causal health effects of military service on the whole population of Vietnam-era veterans—not only draftees but also volunteers, who made up the majority of Americans serving in the military during those years. Previous causal studies have considered only the health of Vietnam veterans drafted into the military.

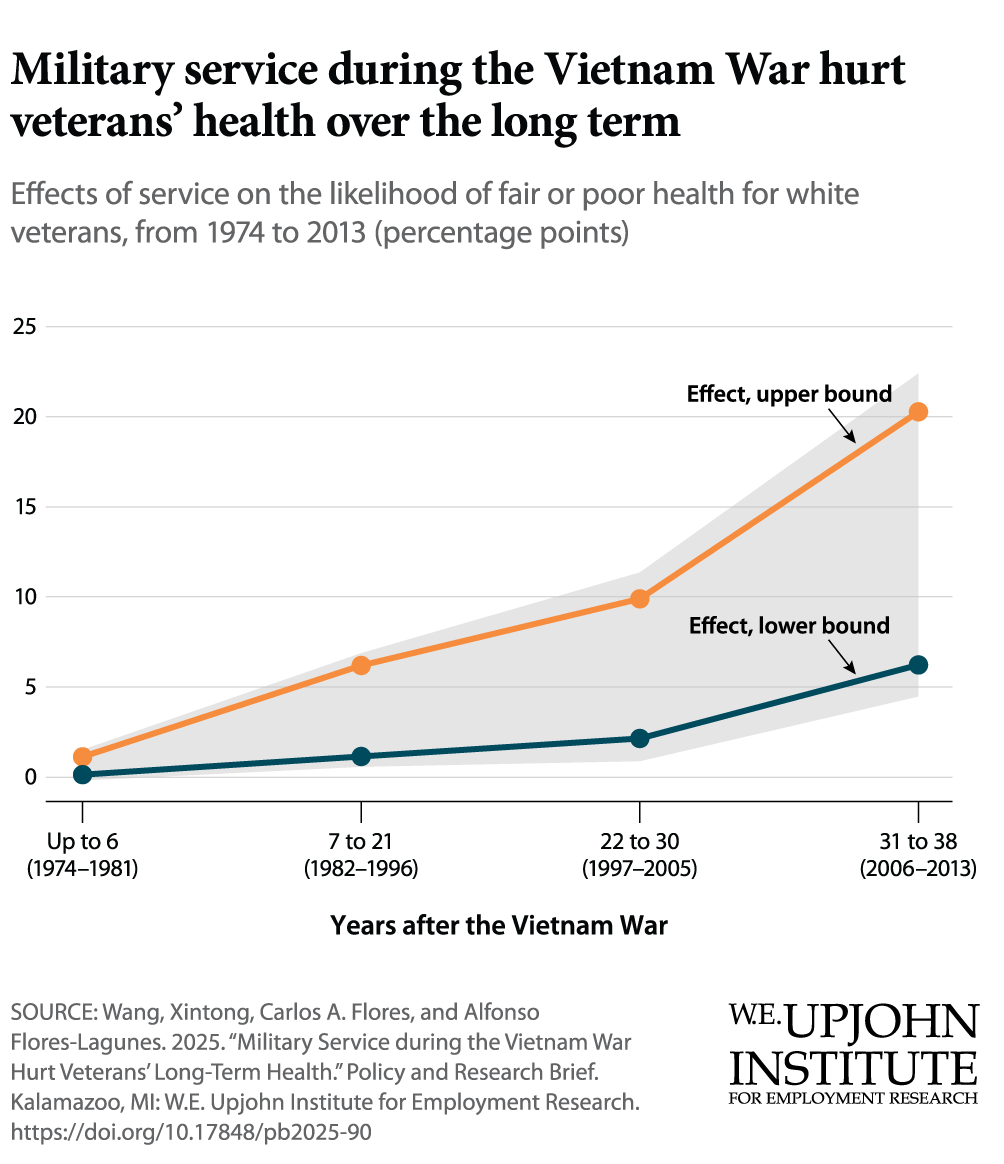

The research, coauthored by the Upjohn Institute’s Alfonso Flores-Lagunes, presents clear evidence that military service was detrimental to service members’ health. However, the negative health consequences did not show up right away: For up to six years after the war ended in 1975, the only obvious effect was increased incidence of smoking. But harmful consequences did appear over time, with a history of military service giving rise to statistically significant increases in diabetes; joint, neck, and back problems; depression; and an array of other maladies.

And mortality risk for veterans loomed: By 2011, 36 years after the war’s end, white veterans were significantly more likely—by at least 22.2 percent—to have died than their peers who had not served in the military. (Outcomes were similar for Black veterans.)

Earlier studies on this topic found that Vietnam veterans who served because they were drafted did not show detrimental health effects from military service. However, these veterans represent only about one quarter of all veterans. In order to establish whether military service adversely affects health, the researchers set out to study the entire population of Vietnam-era veterans.

They used data from the 1974 through 2013 waves of the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), which surveys medical conditions and health. The survey allowed them to consider causal effects of military service on health outcomes for all male Vietnam-era veterans—both draftees (“compliers” with the draft lottery, whose birthdates indicated whether they served) and volunteers.

A draft lottery for the war was held in 1969 and repeated in 1970 and 1971. However, by far the majority of servicemen during those years—above 70 percent—were volunteers, not draftees. In all, almost 9 million Americans served in the armed forces during that era, in Vietnam or elsewhere. This cohort formed the population of the study.

The U.S. government has faced increasing costs of care and disability payments to veterans, driven especially by Vietnam-era veterans. By 2018, almost one-fourth of living Vietnam-era veterans, numbering 1.3 million, were getting disability benefits averaging $18,000 a year. Observers have questioned whether veterans’ benefits in the U.S. are too generous. These findings indicate that the rise in veterans’ compensation has likely stemmed from their declining health over time as a direct result of their military service.

Earlier research had relied solely on draft compliers because of the difficulty of estimating what the health of volunteer veterans would have been, had they not served. For compliers, the comparison is easier: Researchers could compare those who served because they were draft eligible with those who did not serve because they were draft ineligible, benefiting from a fortuitous birthdate excusing them from service.

To overcome this difficulty regarding volunteers, the researchers used a statistical method that, with minimal assumptions, sets bounds on the causal effect of military service for all veterans. Instead of yielding a single estimated effect, it established a range of values into which the true effect falls.

The policy brief to the full paper is called Military Service during the Vietnam War Hurt Veterans’ Long-Term Health, by Xintong Wang, Carlos A. Flores, and Alfonso Flores-Lagunes.