Unemployment insurance provides workers who lose jobs a portion of their previous income as they look for their next jobs. Governments hope workers spend little time receiving unemployment benefits before securing a new – and ideally higher-paying – job.

At certain times, especially during economic downturns, governments look to expand unemployment benefits. Giving money to people without jobs helps them meet basic needs and boosts consumer spending at a time when businesses are suffering.

There are several ways to expand benefits. Governments might send bigger unemployment checks or they might lengthen the maximum time people can stay on unemployment, although these options could keep people out of the workforce longer.

New research sponsored by the Upjohn Institute’s Early Career Research Awards program focuses on another approach: loosening the criteria for who gets to claim unemployment benefits. Approving claims that otherwise would have been barely denied gets benefits to more people while costing the government less than the other options.

Currently, about 10 percent of people applying for unemployment benefits are denied because they are judged to be at fault for the job loss. But some unemployment offices are stingier than others, rejecting borderline claims that more lenient offices would approve.

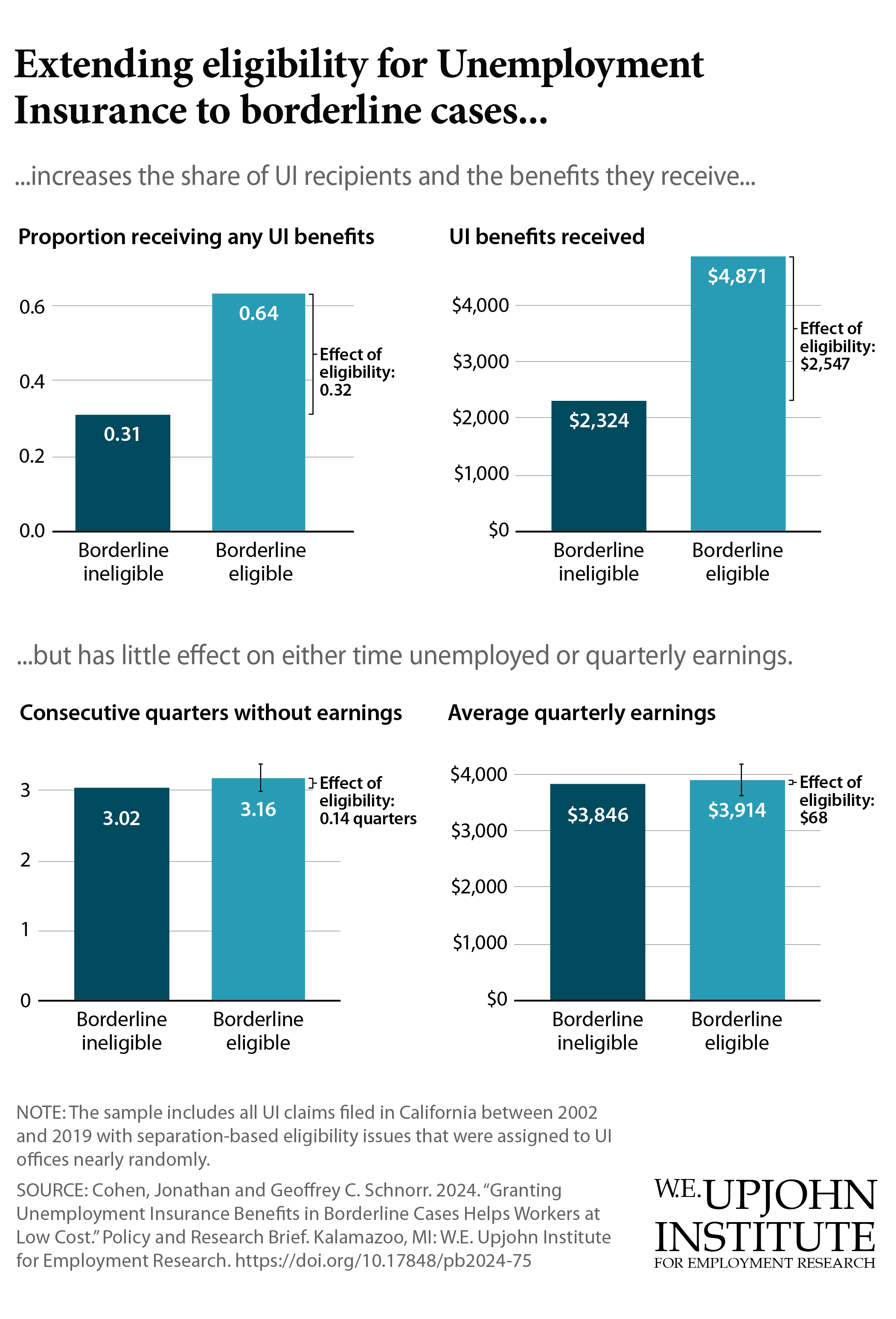

Researchers Jonathan Cohen and Geoffrey Schnorr focus on claims that could have gone either way. They find that expanding eligibility to borderline claimants denied by stingy offices only slightly increases the time people stay out of the workforce and has almost no effect on their quarterly earnings.

What it does do is get more people receiving benefits for less cost to the government than other ways to expand unemployment insurance. Each $1 paid to borderline-claim unemployed people costs the government an extra 19 cents, largely from people delaying their return to work. But increasing benefit checks or the length of time people receive benefits cost the government an extra 67 and 96 cents, respectively.

These differences don’t account for another money saver: workers denied benefits often appeal the decision and the appeals are expensive to process. Workers who are approved for benefits don’t appeal, resulting in additional savings to the government

Cohen and Schnorr conclude that policymakers seeking to expand benefits should look to unemployment insurance eligibility criteria before reconsidering benefit amounts and durations.