November 13, 2025

Falling local population presents an ever-growing problem for small communities. In the decade between 2010 and 2020, the Census Bureau reported that more than half of the counties in the United States declined in population. Until now, most economic models have examined these losses principally in terms of net out-migration: i.e., more people choosing to move out of a county than to move in, their exodus prompted by lackluster wages, a dearth of amenities, or other factors.

Having fewer people living in a place presents all sorts of fiscal problems. With a shrinking tax base, local governments have difficulty paying pensions and maintaining infrastructure. New businesses are leery of setting up shop in a place with a declining labor force. Conversely, population growth, even if slow, tends to stabilize a community, helping it to stave off the vicious cycle of higher taxes for lesser services.

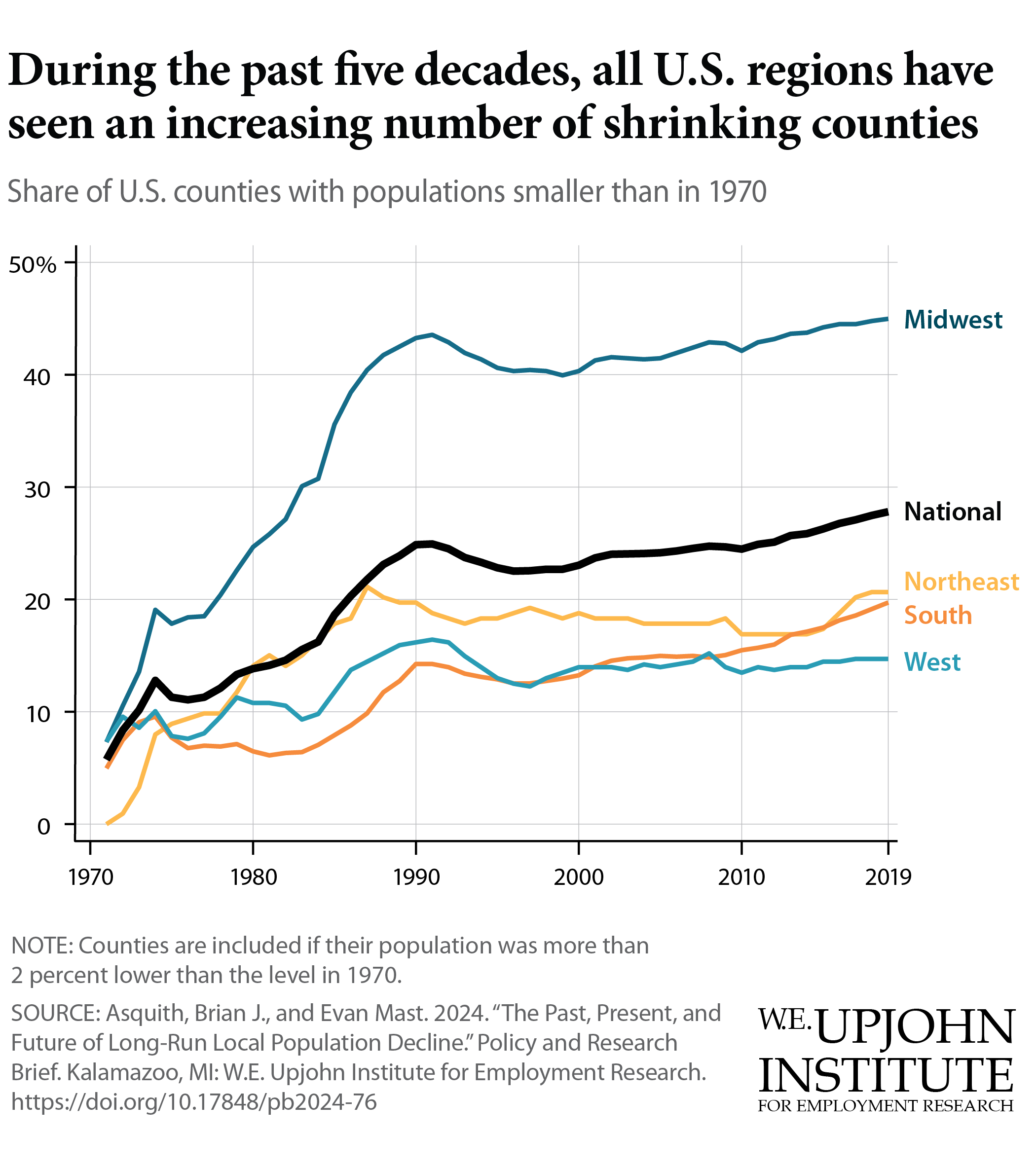

The decade-after-decade rise in the percentage of counties losing population has spawned plentiful research showing that people move for better wages and amenities, and that these trends are increasing, resulting in population pockets that have been “left behind.” Far less common has been research exploring the combined impact of out-migration and a declining birth rate—the nexus of a new research paper by Brian Asquith of the Upjohn Institute and Evan Mast of Notre Dame.

In Regional Science and Urban Economics, economists Asquith of the Upjohn Institute and Mast of the University of Notre Dame offer a more nuanced take than their predecessors: they contend that the net out-migration rate has not increased over the decades; rather, it has remained more or less steady. What has changed has been the birth rate.

In short, a plummeting birth rate in these places has meant that new births no longer routinely surpass out-migration, in contrast to the past, when births would help steady the numbers and even lead to small population gains. Hence, even relatively low rates of net out-migration now lead to falling county population numbers.

Asquith and Mast’s analysis relies on historical data to explore how population growth relates to birth, death, and net-migration rates from 1970 to 2019. A “decline” is measured as at least a 2 percent drop in population, to allow for census counting errors. The percentage of counties falling below this threshold rose for each decade as birth rates dropped dramatically. However, mortality in the counties remained steady, and out-migration was fairly constant at just below zero.

As fertility has fallen, the percentage of counties losing population rose from 22 percent in the 1990s to 35 percent in the 2000s, to more than half now. Overall, for the half-century from 1970 to 2020, nearly 30 percent of counties lost population, despite the U.S. population overall growing by two-thirds.

To help quantify how important the drop in birth rates has been over the long run, Asquith and Mast constructed a model to simulate what county populations would look like today if birth rates were held at 1970 levels. Under this scenario, the median county’s population would have been 32 percent higher in 2019 than it actually was.

In fact, among counties that dropped in population during that half-century, a majority—58 percent—would have grown. However, it was mainly urban and suburban counties that saw their declines reversed in this simulation, indicating that net out-migration hits hardest in rural areas.

The authors further adapted their model to project into the future, until 2070. The model suggests that 51 percent of counties will suffer population decline by more than 2 percent, even if fertility rates rise as the Congressional Budget Office projects. The projection model suggests that recent demographic patterns will only intensify, leading to population gains concentrated in a much smaller number of counties, with the majority of counties, largely rural, suffering persistent decline.