By Michael W. Horrigan, President, Upjohn Institute for Employment Research

September 29, 2025

In recent weeks, the Trump administration has argued that the size of revisions to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) payroll jobs data are too large to be believed, are evidence of manipulation for political purposes, and underscore the need to modernize BLS.

The purpose of this essay is to explain why BLS employment data are revised and to argue that their sizes are indeed concerning, not because of political manipulation but for what they mean for the U.S. economy. I also want to press the case that BLS does need more resources to continue to improve the quality and timeliness of its estimates.

For full disclosure, I worked at the BLS for 33 years, running the inflation and employment/unemployment measurement programs for 10 and 6 years, respectively. However, this is not simply a spirited defense of family turf. Rather, as my training at BLS taught me, I want to address my concerns in a manner that is as objective, nonpartisan, and transparent as possible, including noting where BLS can make improvements in both data collection and reporting.

The administration’s concerns have focused on the Current Employment Statistics (CES) survey, particularly two recent revision episodes: those announced in the July 2025 Employment Situation release and the preliminary benchmark revisions announced on September 9. Let’s examine each in turn.

Revisions to the May and June payroll estimates

In the July release, BLS revised its estimate of payroll employment change for the prior two months sharply downward:

- May’s gain was revised from +144,000 to just +19,000, a reduction of 125,000.

- June’s gain was revised from +147,000 to +14,000, a reduction of 133,000.

These revisions were striking. Their size led the White House to accuse BLS of manipulation and coincided with the dismissal of then-Commissioner Erika McEntarfer. What did not escape the notice of economists, however, was that the revisions signaled a significantly weakening labor market, including a first closing employment change of only +73,000 jobs in July.

Why do revisions occur?

The CES is a large survey—121,000 employers covering about 631,000 worksites—and it takes time to collect responses. BLS allows three months for reporting. About 60 percent of firms respond by the first closing (the basis for the initial release), 90 percent by the second, and 95 percent by the third. Revisions simply reflect the incorporation of these later reports, which improve accuracy.

First-closing response rates have slipped from around 70 percent pre-pandemic to 60 percent today. That decline increases variance in the preliminary estimates. For June 2025, about 40 percent of the downward revision from first to second closing came from late reports in state and local government education. Other industries also revised downward, producing the overall –133,000 change.

Seasonal adjustment also contributes to revisions. Because employment follows predictable seasonal patterns—teacher layoffs in summer, holiday retail hiring, winter slowdowns in construction—BLS adjusts to isolate true cyclical trends. Between the second and third closing, when over 90 percent of responses are in, most revisions come from re-estimating seasonal factors with the new data.

Are these revisions historically unusual?

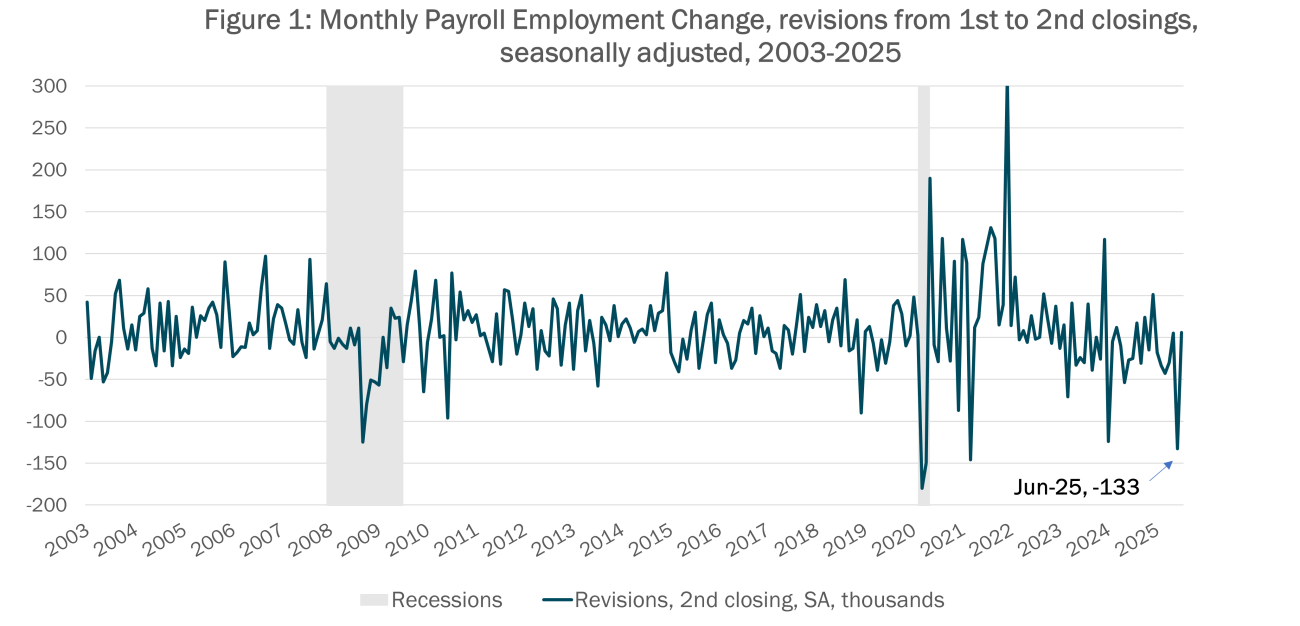

The administration has argued that these were the largest revisions since 1968 (Kevin Hassett, Meet the Press, August 3rd, 2025). That is not quite accurate. The June downward revision of 133,000 was the sixth largest in absolute value since 2003, when probability-based sampling was introduced into the CES. However, if you exclude the pandemic months, it was in fact the largest since 2003 (see figure 1).

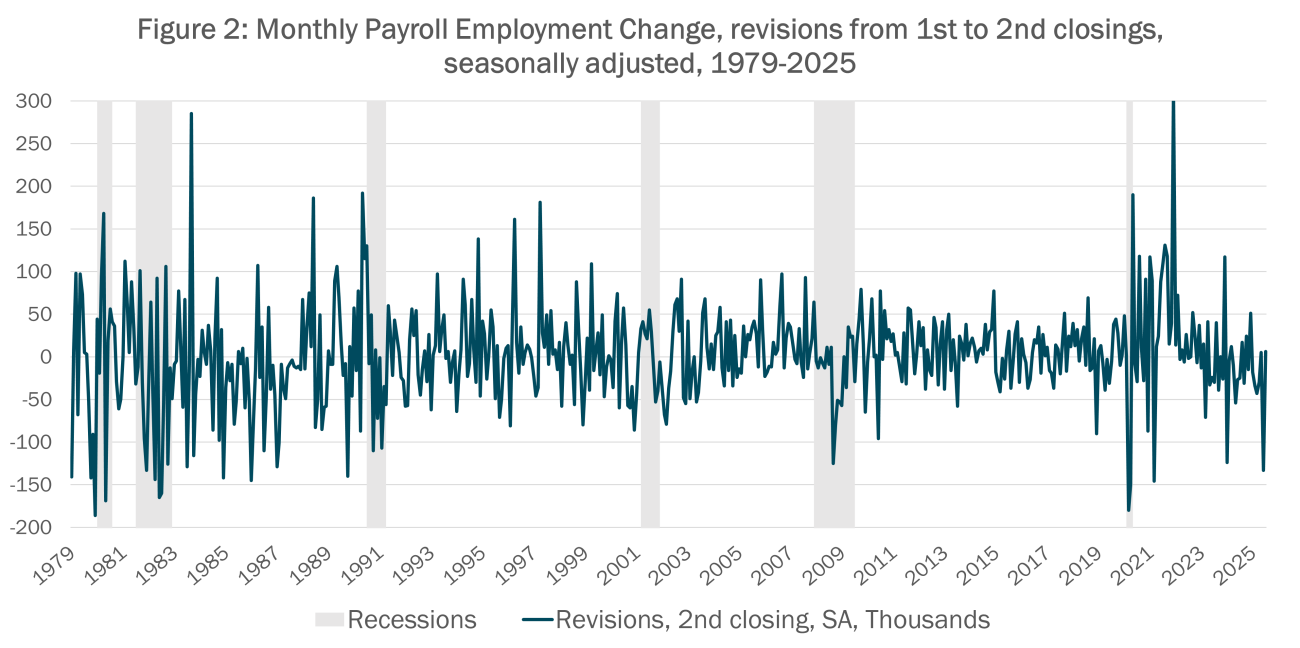

Prior to May 2003, CES used quota-based sampling, with the goal of achieving 40 percent employment coverage for each reporting month. Revisions were more variable under quota-based sampling, and the June 2025 revision from first to second closing ranked 23rd in absolute value since 1979. If you only include negative revisions, the June 2025 revision ranks 14th (see figure 2).

More important than the ranking is the pattern of revisions. Nearly all the largest downward revisions from first to second closing have occurred when the economy was turning toward or in a recession: 1979–82, 1989–90, 2008–09. The brief recession of 2001 is an exception to this pattern. The June 2025 revision fits this historical profile, suggesting that it may be less an anomaly than a signal of a labor market weakening toward contraction.

Can BLS improve first estimates?

While it is important to correct the record and put the size of the June 2025 revisions in historical context, the fact remains that the revisions were relatively large, raising the question—are there any enhancements that BLS can make to improve the accuracy of the estimates at first closing and reduce subsequent revisions?

One straightforward idea is to delay the release of the monthly CES data by a week or two, extending the reporting period. Currently, CES collection generally stops the Friday before the Employment Situation release. When release dates fall early in the month, collection may end before the reference month has ended. Extending collection could substantially raise first-closing response rates, reducing revision size. The jump from 60 percent to 90 percent between first and second closing suggests how much improvement is possible.

With additional resources, BLS could also expand its use of automated reporting systems. The agency has already modernized CES collection and is transparent about its methods. Today, about 60 percent of responses come via preset electronic files from large firms, 30 percent through web forms from smaller firms, and 10 percent through computer-assisted telephone interviews. One way to improve timeliness could be to have more respondents transmit their files electronically.

Similar innovations are emerging elsewhere in the federal statistical system. For example, the Census Bureau, working with Intel, has piloted large language models that extract data directly from company databases and populate survey forms automatically. In the pilot, the firm reduced its quarterly reporting time from more than 200 hours to just 30 minutes. Demonstration projects like these show how advanced automation could transform response rates and reduce revisions if extended to BLS surveys. Of course, these innovations require an investment in resources.

Preliminary Benchmark Revisions

The second flashpoint has been the September 9 preliminary benchmark revision, which showed that CES employment in March 2025 had been overstated by 911,000 jobs as compared to the universe count of employment from Unemployment Insurance (UI) records in the BLS Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages. The size of this revision fueled renewed accusations of manipulation, including by the Secretary of Labor.

Why does such a gap exist between CES survey estimates and the universe count from UI records? The key issue is business births and deaths. The CES survey cannot observe new businesses, nor can it instantly recognize when firms close.

To bridge this gap, BLS uses the birth-death model, which has two components:

- Proxying births from deaths. This first component leverages the general finding that in any given month, employment gains from business births roughly equal employment losses from deaths. Firms that report zero employment this month (apparent “deaths”) are used as a proxy for unobserved births. Their prior employment is adjusted by the trend from continuing firms. This first component accounts for most net birth-death employment.

- Historical residual adjustment. The second component takes into account the historical differences between the estimated monthly employment from the CES and from the full universe count, which reflect the extent to which average employment gains from business births differ from average employment losses from business deaths.

In normal times, this approach produces small differences. But in downturns, the assumption that births offset deaths often breaks down. If employment losses from firm deaths begin exceeding employment gains from new firms, using deaths as a proxy for unobserved births will result in an overestimation of job creation.

For example, in 2009, the benchmark adjustment, reflecting economic activity from April 2008 to March 2009—that is, the beginning of the Great Recession—was –902,000.

Indeed, the “controversy” surrounding the preliminary benchmark adjustment of –911,000, reflecting the difference between the CES estimated employment and the full universe count in March 2025, should be a clarion call of concern over the fact that labor markets have greatly weakened in the last year. In addition, the benchmark adjustments of –266,000 in 2023 and –589,000 in 2024 suggest that the labor market has been growing increasingly weak for the last three years.

Can the Birth-Death Model Improve?

BLS does not stand still. For example, the pandemic resulted in larger birth-death forecast errors as measured by the difference between the estimated and the universe count of employment each month. This led BLS to incorporate more recent sample information into the forecasts in 2024, update this modelling component quarterly instead of annually, and include a regression component to its time series model in 2024. BLS staff has done and will continue to do high-quality research to improve the components of the birth-death model. As well, additional resources could also be used to shorten the current lag of six months between the publication of CES estimates and the availability of the full universe file of UI records.

Final Thoughts

The administration’s emphasis on the size of BLS revisions, and its portrayal of them as evidence of manipulation or untrustworthiness, is a disservice to the American people. I believe strongly in the integrity of the BLS and its staff, and while there is always room for improvement, a point on which I can agree with the administration, I am concerned about the lack of trust that is being created by these false accusations.

Revisions are not evidence of bias. They are the transparent process of refining estimates as more information becomes available. But the size of the recent revisions does matter: not as proof of corruption, but as evidence that the labor market and the U.S. economy may be slowing significantly, and as a reminder that BLS needs the tools and resources to modernize.